Some text are said to have influenced a whole generation; some are even called centennial. But the content of two books have been infusing our so called occidental couture and particularly art and literature over the span of the last two thousand years: this is the bible and Ovid’s Metamorphoses

|

| Claude Lorrain: “Ariadne auf Naxos”. „A new god comes along – and silently we are devoted!” mocks Zerbinetta in Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s libretto to Richard Strauss’ Opera, when Ariadne lets herself get comforted by Bacchus – and obviously has already forgotten Theseus. And Bacchus puts Ariadne’s crown as constellation into the sky and thus sets the faithful spinner an everlasting memorial: desertae et multa querenti amplexus et opem Liber tulit, utque perenni sidere clara foret, sumptam de fronte coronam inmisit caelo: tenues volat illa per auras dumque volat, gemmae nitidos vertuntur in ignes |

|

| In 1606 Adam Elsheimer painted this illustration to “Acis and Galatea”. Elsheimer adopts the great perspective of Ovid’s landscape portrayals and completely abandons to show any persons. The painting, which is also titled “Aurora”, is regarded as the first pure landscape painting – so modern that later coevals still put figures to the left side. |

|

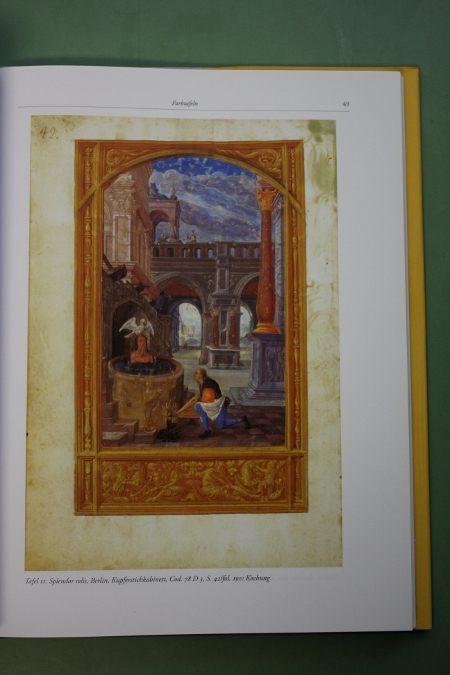

| The alchemical luxury manuscript Splendor Solis from the 16th century – shown is the copy of Berliner Kupferstichkabinett – takes a path to the Philosopher’s Stone along twenty two miniatures, like gates, framed by stonework, giving in each case a view into the next room of chymical enlightenment. Also the miniature to the 11th gate, Purification in the tub of renascence, points directly to Ovid: the relief in the base of the column on the right shows Pygmalion, creating the woman of his dreams. The alchemical text to this plate gives a paraphrase of ‘Medea and Pelias’: The seventh parable: OVID the old Roman, wrote to the same end, when he mentioned an ancient Sage who desired to rejuvenate himself was told: he should allow himself to be cut to pieces and decoct to a perfect decoction, and then …” Admittedly Pelias did not fare well with that: barbarous Medea instead of her potion had put only noneffective herbs into the kettle! |

|

| Nicolas Poussins “Midas and Bacchus” from the Munich Pinakothek can be seen in Reiner-Werner Fassbinder’s drama “The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant” declining to a picture wallpaper in the protagonist’s bedroom. The rich fashion designer Petra von Kant can thus easily be seen as modern variety of the king who would let everything he touched turn into gold, but at the same time almost died of thirst and hunger. |

|

| Polyphem / Triumph of Galatea by Raffael and students. Agostino Chigi, the richest man of the 16th century erected his residence in rome on the left bank of the Tiber River, which is today called after its later owner “Villa Farnesina”. Chigi had built the palace for himself and his concubine , the Venetian Francesca Ordeaschi. The remarkable with this liaison is, that it is supposed to be a real love attachment – hardly befitting his rank at all: the bride, a notorious courtesan – this love was finally legitimated to matrimony by pope Leo X. Chigi let his Villa stock by Raffael an his school with frescos to Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The continuous motive: love. About the most famous is Raffael’s “Triumph der Galatea”. Ovid’s Episode is on the one side full of aerial beauty – realized very well in Elsheimer’s painting, on the other side we find also moments of even humorist punch line: When the hulking cyclops Polyphem tries to get his adored Galatea – the ‘milky white’ how the name in deed reads verbatim – on his side with sweet words: “More white then the leaf of snow white privet, Galatea, more blooming then the meadows, more slender then the alder, … , more wanton then the tender kid (well, this means not child but goatling; jb), more smooth then shells, continuously rubbed by the see, … , more clear then ice, more sweet then grape through ripe, more soft then down of cygnet and more white then cheese …” “Candidior folio nivei Galatea ligustri, floridior pratis, longa procerior alno, …, tenero lascivior haedo, levior adsiduo detritis aequore conchis, … lucidior glacie, matura dulcior uva, mollior et cycni plumis et lacta coacto; …” |

|

| “Metamorphose in der Not” (Metamorphosis in an Emergency) that was drawn by Paul Klee 1939 shortly before his dead, pictures the hope for liberation from the incurable body, for a transformation into another beeing – by the mercy of the gods, like in Ovid. Klee died 1940 after a long suffering from a cureless illness. |

Written early in our calender era, Ovid’s “Fifteen books of transformation” stayed more or less permanently to the 19th century the raw material for literature, theatre, sculpture and particularly painting. Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakespeare to Ted Hughes and the Simpsons, Adam Elsheimer, Claude Lorrain, Peter Paul Rubens to Ian Hamilton Finley; thousands works of art.

Being translated into many medieval local languages as early as the 13th century, it is in fact mostly tales from the Metamorphoses, which are commonly taken for the “Greco-Roman Mythology”.

No wonder, that painting in particular was influenced to such an extend by Ovid. The stories are so immensely pictorial, even iconic, when they tell us of more then two hundred fifty characters changing their Form (or being changed into a new form) – a man, faun or nymph becoming rivers, mountains, all kinds of animals. But the quality of Ovid’s storytelling and poetry is not limited to catchy narration of famous or remote myths.

Typically the single episode of a metamorphosis begins in a great long shot, in which our view floats high above the landscape that fades away in the distant haze. The location of the story forms randomly at the edge of this picture, the heroes appear and we come closer and closer until we get totally involved with the thought and feelings of the actors. And these feelings motivate the whole behaviour of the persons, who in this very moment strive towards the turning point of their life. In almost all tales the main driver of the actions is love. Unmet love, jealousy of the happily loving, or the love of a mother- or father; the end is in most cases tragic and full of cruelty – but not rarely the unfortunate heroes get saved from their distress by a forbearing godhood.

***

On top of this first narrative level with the three perspectives of the story – psychological inner life of the heroes, the plot, and the description of the location and the landscape – there lies a second, metaphoric layer. We catch through the psyche of the acting persons the generally human: desire, joy, pain, grief and solace. Good and bad are not frequently clear, mostly we can rather feel with both sides, for Ovid portrays his staff in such an empathetic way and even invokes for compassion directly within the text.

A third level can be read allegorically. To conceive our environment we use pictures because the noumena are not comprehensible for us directly. Nietzsche speaks of a “Metamorphosis of the world into men”. Almost all of Ovid’s stories of transformation explain pictorially geographical, biological or physical phenomena and make abstract ideas and philosophic terms visible.

Transformation as the principle of creation became finally the framework of alchemy in the middle ages and the early modern times. Ovid’s Metamorphoses were read by the adepts of the chimical arts as the transmutation of matter from one state into the next. Allegorical schemes by which we can cognize the world are offered by the fifteen books of transformation even today. For example our idea of “Chaos” as abstract concept is directly deviated from the impressive beginning of the first book:

Ante mare et terras et quod tegit omnia caelum /

unus erat toto naturae vultus in orbe, /

quem dixere Chaos: rudis indigestaque moles, /

nec quicquam nisi pondus iners congestaque eodem /

non bene iunctarum discordia semina rerum.

Before there was the land and the sky that covers all /

nature had only one face all over the world /

this was called Chaos: a rude, unordered mass /

nothing but inert weight and on a heap /

the not well assembled, seeds of things being at strife.

***

The numerous literary translations of the Metamorphoses are often far more stuck into their time than the original. Of course for example the adaption by Arthur Golding has been highly influential for the English literature but even for the English language which tends to be similarly brief compared to Latin, words and insertions are needed to fill the metre. Much feels unfresh today, a bit dusty. Isn’t it remarkable how the centuries since Ovid’s time became outdated and sagged into history!

Modern translation that keep to the text are better suited, alone for the possibility to point out poetic specialities that always are left out by literary adoptions.

Ovid’s own words are beautiful and touching even after two thousand years.

One reply on “Ovid: Metamorphoses”

No wonder why Themelis Cuiper’s SocialGarden interviews of socialmedia & smo tweeted a hyper link to your web-site, you must be doing a brilliant job as he is pointing towards you! :d